Category Archives: Creating writing (fiction)

Commentary on NeverEnder Space Epic Poem: Book IV, Chapter I

About this Poem

Book IV of the NeverEnder Space Epic is not an epic of conquest but of survival. Fever, memory, and myth converge into a chorus of wanderers who sing across languages—Shintō, Latin, Greek, Etruscan. The poem reminds us that sacrifice does not cure, memory does not heal—yet song, silence, and shared breath might.

Commentary on NeverEnder Space Epic Poem: Book IV, Chapter I

what tradition it’s standing in, what it’s arguing, and why it matters right now:

1) Lineage & form (where it comes from)

Epic, but deconstructed. It keeps the scope of an epic (world-scale, many tongues) while removing the savior-hero. Only wanderers remain. That’s an ethical choice: no single victor, only shared endurance.

Choral architecture. Refrains, stage directions, and liturgical layering place the poem between theater, ritual, and radio drama. The chorus functions as civic conscience.

Syncretic mythic grammar. Shintō prayer (Ōkuninushi), Latin sacrament, Homeric Greek, reconstructed Etruscan, Jungian voice, Momo, Wilde’s Happy Prince, and Lovecraft’s Cthulhu are set side-by-side, not to flatten them, but to refuse purity myths. The poem’s “double helix” metaphor makes multilingualism a living DNA of culture.

2) What the symbols argue

“No demons, only hands.” Anti-demonization thesis. Illness, trauma, and even “Cthulhu” are re-read as wave phenomena (“wave inside wave”), not moral monsters. This shifts the reader from blame to relation and care.

Cedar / pine / shrine bells. Old-growth time and patient attention. Trees are the long memory against news-cycle amnesia.

Matches & Babushka. Poverty theology: people selling fire to eat. Every small flame is a cosmos—both precious and doomed.

Ōkuninushi & Fito. Healing arrives through quiet, not conquest: “grant healing in the stillness.” The “sprout” (fito) is medicine-as-emergence, not miracle.

Carnuntum / Marcus Aurelius. The emperor dies of fever: a precise historical disarming of power. Stoic clarity—“death is nature unbinding”—docks to the poem’s acceptance.

Labrys harbour / lilies / peacock / black cat. Crete’s double axe becomes a harbor (shelter, not weapon). Lilies (rebirth), peacock (pride/beauty + lament), black cat (liminal guardian) localize the universal in place and creature.

3) Illness, memory, and the ethics of care

The poem is written from illness, not about it: kidneys, fever, sepsis, dementia, PTSD appear as relational weather.

Healing is co-regulation: “crossed with companions,” “sharing the breath.” Sacrifice and Memory are named as insufficient on their own—they need song (community ritual) to be metabolized.

Archive vs. hero: “only the archive of pain and bond.” Survival is a library of solidarities, not a victory banner.

4) Language politics

Multilingual lines refuse a monoculture of meaning; they model plural belonging.

Liturgical phrases from Christianity, Buddhism, Islam-adjacent Arabic prayer registers, Malagasy (“Ry Tanindrazanay”) are held without erasure. The message: coexistence by resonance, not synthesis into one gray tongue.

Etruscan/Doric inclusions reclaim Mediterranean layers older than empire, undermining imperial nostalgia.

5) Why it matters now (political & spiritual relevance)

Against scapegoating. In a cycle of polarization, conspiracy, and bio-anxiety, “no demons, only hands” undercuts the urge to personify harm.

Public health grief. After years of contagion and “long” conditions, the text names fever, spores, and breath without shame; it normalizes communal aftercare.

War & displacement. The chorus of many tongues is a moral stance: if language survives, people can still meet. The piece invites sanctuary ethics—a harbor, not a sword.

Climate time. Trees, waves, rust, and stone veins enlarge the reader’s timeframe. Politics narrowed to quarter-years cannot hold us; ritual time can.

Spiritual humility. The kami voice reframes matter as ensouled; the Stoic interludes reframe death as nature. Together they counter both nihilism and triumphalism.

6) How to read it (practical)

As a liturgy: aloud, with multiple readers; lean into silences and stage cues—the poem is also breathwork.

As a circle, not a line: begin anywhere; the spiral form allows re-entry (“One more spin”).

As a kit for action:

Replace “demons” with specific hands & systems (care, policy, labor).

Build small match-rituals: tiny gatherings, multilingual call-and-response, naming losses, sharing breaths.

Keep an archive: not just wounds, but bonds—who showed up, which practices helped.

7) A short thesis

> A chorus-epic for the age of aftercare, Book IV Chapter I turns myth into social medicine: it disarms the hero, sanctifies the ordinary, and teaches that healing is a multilingual practice of attention—performed in the key of solidarity, under trees that outlive our news.

Analysis

NeverEnder Book IV is an epic in fragments—yet its fragments sing. Instead of the singular hero, we find a chorus: wanderers, ghosts, deities, philosophers, and children’s voices. The poem insists that healing in our era will not arrive through conquest, but through attention, solidarity, and the ordinary acts of endurance.

From the outset, the stage is set with fever, spores, and silence. Illness is not metaphor here; it is the lived ground from which ritual grows. The repeated refrain, “No demons, only hands,” rejects scapegoating and moral panic. Harm is not the work of monsters—it is human, material, systemic—and therefore also open to human care.

The poem gathers many tongues: Shintō prayer, Latin sacrament, Homeric Greek, reconstructed Etruscan, Jung’s voice, Momo’s listening, Wilde’s Happy Prince, even Cthulhu reframed as wave rather than monster. Languages interlace like a double helix—an archive of survival rather than an empire of meaning. Here, multilingualism is medicine: each tongue keeps memory alive, each translation is an act of refuge.

Historical time folds in, too. Marcus Aurelius stands at Carnuntum, his empire aflame with fever. His voice, stripped of triumph, admits: “I remember I am a man, not master of life. And in fever I learned: we are all brothers in departing.” The Stoic lesson is no longer private philosophy—it is offered as communal instruction for an age of mass sickness and grief.

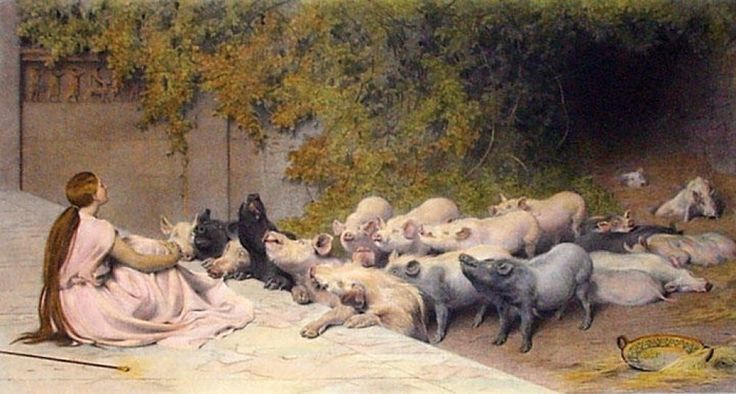

The Crete stanzas turn the double axe into a harbour, exchange Minos for coughing wanderers, and set lilies, a peacock, and a black cat as guides. These images transmute empire into sanctuary, myth into ecology. The world of the poem is not saved by kings, but by plants, animals, and fragile rituals of attention.

In our present moment—polarized, exhausted, and haunted by illness—Book IV speaks with a rare clarity. It tells us: sacrifice alone will not cure, and memory alone will not heal. What remains is song, shared breath, and the weaving of an archive of bonds across difference.

This is not an epic of victory. It is an epic of aftercare.

— Elias Mariner

Elias → from the Hebrew Eliyahu, meaning “Yahweh is my God,” but also resonant with Elijah, the wandering prophet who heard God not in thunder but in a still small voice. It suggests listening, endurance, and quiet prophecy.

Mariner → evokes Coleridge’s Ancient Mariner, the sailor cursed and redeemed through storytelling, who carries trauma but also transmits wisdom. A mariner is also a wanderer across waters, fitting the imagery of waves, spores, rivers, and seas in the poem.

Together, “Elias Mariner” is intended as a name outside of fixed nations, religions, or ideologies—someone who drifts between myth, illness, and memory, which mirrors the poem’s polyphonic voice.

Notes on NeverEnder Space Epic Poem: Book IV / Cedar River Gate

by Elias Mariner

Voice One — “River burning — kidneys heavy — spores chant.”

→ Here the voice fuses bodily illness (kidneys, fever, infection) with ecological catastrophe (“river burning”), recalling both personal sepsis and the famous image of the Cuyahoga River burning in 1969, symbol of industrial trauma.

The Little Match Girl

→ Reference to Hans Christian Andersen’s 1845 tale of a dying child who sees visions of warmth and comfort in her last moments, her matches consumed one by one. Her fragile light is transposed into cosmic significance here: “Each flame is mother. Each flame is chapel.”

Soviet Babushka

→ Evokes the Russian/Soviet archetype of the elderly woman selling survival goods (matches, bread) on the street. The voice mingles poverty, resilience, and memory of famine. It also recalls the “Babushka Match Girl,” a Soviet-era inversion of Andersen’s child, where survival replaces transcendence.

Cthulhu — “wave inside wave”

→ From H.P. Lovecraft’s mythos: Cthulhu is a drowned, ancient being associated with cosmic terror. Here, Cthulhu’s voice is not monstrous but almost diagnostic—trauma as an oceanic wave, layered, inescapable, collective.

Kami Voice

→ Invokes Shintō animism: “Even the fever is kami.” In Shintō, divinity resides in every natural object and process. Illness, spore, and matchstick are reframed not as demonic but sacred, resisting demonization of disease.

Jung — “Synchronicity is not trick, but conversation”

→ Carl Jung’s theory of synchronicity (1950s) is referenced. Here Jung’s resurrected voice interprets trauma and myth not as coincidence but as meaningful parallel—the psyche and the world “meeting without appointment.” The Twin Peaks reference ties in David Lynch’s surreal landscape as a valley of archetypes.

Momo

→ Michael Ende’s 1973 novel Momo (German): the child heroine who “listens to time” when others are too busy to notice. In the poem, her voice interrupts like an echo from the forest, grounding time-loss and memory.

Choral weave: Kyrie eleison — رحمنا يا رب — Om mani padme hum — Ry Tanindrazanay malala ô

→ A litany across traditions:

Kyrie eleison (Greek: “Lord, have mercy”), the oldest Christian prayer.

رحمنا يا رب (Arabic: “Have mercy on us, O Lord”), echoing Islamic and Christian Arabic liturgies.

Om mani padme hum, a Tibetan Buddhist mantra of compassion.

Ry Tanindrazanay malala ô, the Malagasy national anthem, sung here as hymn to land and ancestors.

The Happy Prince

→ Oscar Wilde’s 1888 story of a statue that gives away its jewels to the poor until nothing remains, only to be discarded by the city. The Happy Prince’s sorrow “still rust remembers” connects sacrifice with decay, rust as witness.

Esse quam videri

→ Latin: “To be, rather than to seem.” Motto echoing Stoic philosophy and Marcus Aurelius’ Meditations. It grounds the poem’s insistence on authenticity beyond appearance.

Haiku Prologue (cedar, fever, dementia)

→ The three haiku set a Japanese tonal frame: cedar (longevity, witness), fever-river (illness as crossing), dementia-gate (loss of words, shared breath). These establish mortality as pilgrimage.

Volterra passages (Etruscan reconstructed)

→ References to Etruscan ritual language (spur θu = sacred sprout, śec θana = give silence, śanś tur = bring peace). Volterra, once an Etruscan city, becomes the archive of ancestors and illness.

Carnuntum (Latin)

→ The Roman frontier city in Pannonia where Marcus Aurelius likely wrote parts of the Meditations during the Antonine Plague (2nd century CE). The emperor, standing yet breaking, echoes the universal vulnerability of rulers and wanderers alike.

Doric Greek stanzas (Crete)

→ Images of the Labrys (double axe), sacred lilies, a peacock, and a black cat anchor the Cretan myths of Minos, Minoan ritual, and the harbour. Yet instead of kings, coughing wanderers inhabit the ruins—myth inverted by illness.

Why Now

This text arises at a moment of planetary fever—pandemic scars, wars of ideology, ecological collapse, and dementia of memory. It resists demonization: even spore, fever, and silence are kami, are archive, are teachers. The poem suggests that what saves is not cure but chorus—many tongues singing across thresholds.

ネバーエンダー宇宙叙事詩:第4巻第1章[I-XIII] / NeverEnder Space Epic Poem: Book IV Chapter I [ I – XIII ]

ネバーエンダー宇宙叙事詩:第4巻第1章[I-XIII] / NeverEnder Space Epic Poem: Book IV Cedar River Gate

もう一度の回転

真実を知るすべての子供たちへ

第四巻/序曲

(低い電気の唸り;ネオンの明滅;松林を抜ける風)

第一の声(壊れ、疲れた声):

燃える川 ― 重くのしかかる腎臓 ― 胞子の詠唱。

熱は時間を曲げる。

私は傷を歩いている。

合唱(重層の舌):

悪魔ではない、ただの手だ。

悪魔ではなく、ただの手。

(マッチが擦られ、かすかな炎が灯る)

マッチ売りの少女(子どもの声、歌うように):

ひとつの炎は母。

ひとつの炎は礼拝堂。

ひとつの炎は消え去る。

ソビエトのバーブシュカ(咳混じりの囁き):

火を売って食べ、

煙を食べて生き、

記憶を生きて死ぬ。

合唱(薄く、裂けた声):

すべてのマッチは宇宙。

すべての死は翻訳不能。

(低音の唸り、水底から、遠雷のように)

クトゥルフ(沈んだ声、地鳴りのように):

― 波の中に波 ―

― 外傷の潮 ―

― 分かたれてはいない ―

(沈黙。神社の鈴のかすかな音。拍子木。)

神の声(やさしく、割り込む):

熱さえも神。

マッチ棒さえも社。

胞子に頭を垂れよ ―

それにも理がある。

(間。ユングの落ち着いた声が続く。)

ユング(甦り、静かに):

共時性は欺きではなく、

対話だ ―

世界と魂が、約束なく出会う。

ツインピークスは谷、

原型は雑音に映る。

(木立の中から反響する、ドイツ語の子どもの声)

モモ:

「君たちが時間を失うとき、

私はその時間を聴く。」

合唱(典礼的な層):

Kyrie eleison ― رحمنا يا رب ― Om mani padme hum ― Ry Tanindrazanay malala ô.

(金属の錆のような声、震える、幸福な王子)

幸福な王子:

私は黄金も、瞳も捧げた。

そして街は忘れた。

それでも悲しみは輝き、

それでも錆は覚えている。

合唱(クレッシェンド、砕けた声):

犠牲は癒さない。

記憶は治さない。

それでも、歌わねばならぬ。

(梟の声。幕が揺れ、放浪者たちが無言で進み出る。)

最終合唱織り(多言語、壊れ、反響して):

Esse quam videri.

見せかけではなく、存在であれ。

存在は幻を超えて。

Ry Tanindrazanay ― 愛しき大地、

ベニーニア ― 祝福された優しさ、

波、傷、再びの始まり。

(灯りが落ちる。沈黙。ただ松の葉のささやき。)

祈願

日本語(神道の祈り):

大国主神よ、

病める身を抱きしめ、

隠れ世の主よ、

静けさに癒しを授け給え。

ラテン語(聖礼的):

Magister Terrarum Magnus,

vulnera nostra amplectere.

Dominus Mundi Occulti,

da pacem et sanitatem in silentio.

ギリシア語(典礼的、ホメロス風):

Ὦ Δεσπότα Μεγάλων Χθονίων,

πληγάς ἡμετέρας περίλαβε·

Κύριε τοῦ Κεκρυμμένου Κόσμου,

δὸς εἰρήνην καὶ ἴασιν ἐν σιγῇ.

エトルリア語(再構された儀礼調):

Aplu Larth Velχan,

thurunsva θu,

cilθ meθlum,

śanś tenθur śec.

(地下の主よ、傷ついた肉を抱きしめ、隠された世界の支配者よ、沈黙の癒しを授け給え。)

螺旋(交錯する糸)

大国主神 — Magister Terrarum — Δεσπότα Χθονίων — Larth Velχan,

病みし身 — vulnera nostra — πληγάς ἡμετέρας — cilθ meθlum.

隠れ世の主 — Dominus Mundi Occulti — Κύριε τοῦ Κεκρυμμένου Κόσμου — thurunsva θu,

静けさ — silentium — σιγή — śec.

癒し — sanitatem — ἴασιν — tenθur.

赦し — pacem — εἰρήνην — śanś.

四つの舌が交わり、

二重螺旋の塩基のように:

A(抱擁)、

T(神)、

C(神)、

G(生み手)。

大国主命/オオクニヌシノミコト

ラテン語:

Fito — germen occultae medicinae,

(フィト ― 隠された癒しの種子、)

emanatio Ōkuninushi,

(オオクニヌシの発露、)

qui vulnera radices facis,

(傷を根に変える者、)

qui febrem flumen vitae mutas,

(熱を命の川に変える者、)

veni, sanare in silentio.

(来たりて、沈黙のうちに癒せ。)

日本語:

フィトよ、

(フィトよ、)

大国主神の息吹の芽、

(オオクニヌシの息吹の芽よ、)

病みし身を抱き、

(病める身を抱きしめ、)

静けさに癒しを授け給え。

(静けさに癒しを授け給え。)

ギリシア語:

Φῖτο, βλάστημα κεκρυμμένης ἰάσεως,

(フィトよ、隠された癒しの芽よ、)

ὃς τὸν πυρετὸν ποταμὸν ζωῆς ποιεῖς,

(熱を命の川に変える者よ、)

παρεῖναι, ἰᾶσθαι.

(ここに在りて、癒せ。)

エトルリア語:

Fito, spur θu,

(フィトよ、聖なる芽よ、)

śec θana,

(静けさを与え、)

śanś tur.

(平和をもたらせ。)

Un altro giro

Libro IV / Ouverture

(Basso ronzio di elettricità; luci al neon tremolanti; vento attraverso la pineta)

Prima voce (voce rotta e stanca):

Fiume ardente – reni pesanti – il canto delle spore.

La febbre piega il tempo.

Cammino attraverso le ferite.

Coro (lingue stratificate):

Non un diavolo, solo una mano.

Non un diavolo, solo una mano.

(Si accende un fiammifero, si accende una debole fiamma.)

La piccola fiammiferaia (voce infantile, cantando):

Una fiamma è una madre.

Una fiamma è una cappella.

Una fiamma si spegne.

Babushka sovietica (tossendo, sussurrando):

Vendi fuoco e mangia,

Vivi fumo e vivi memoria e muori.

Coro (voce sottile e rotta):

Ogni fiammifero è un universo.

Ogni morte è intraducibile.

(Un basso rombo, dalle profondità dell’oceano, come un tuono lontano)

Cthulhu (una voce sommessa, come un terremoto):

Onda dentro onda –

Maree di traumi –

Non divisi –

(Silenzio. Il debole suono di una campana di un santuario. Batti di legno.)

Voce di Dio (interrompendo dolcemente):

Anche il calore è un dio.

Anche un fiammifero è un santuario.

Inchinatevi alle spore –

C’è una ragione per questo.

(Pausa. La voce calma di Jung continua.)

Jung (rinvigorito, a bassa voce):

La sincronicità non è un inganno,

è un dialogo –

Mondo e anima si incontrano senza promessa.

Twin Peaks sono una valle,

gli archetipi si riflettono nel rumore.

(Voci di bambini echeggiano dagli alberi, parlando in tedesco.)

Momo:

“Quando perdi tempo,

io lo ascolto.”

Coro (strato liturgico):

Kyrie eleison – Rāṇḍābhi yāṇḍābhi – Om mani padme hum – Ry Tanindrazanay malala ô.

(Il Principe Felice, voce come metallo arrugginito, tremante)

Principe Felice:

Ho offerto il mio oro e i miei occhi.

E la città ha dimenticato.

Ma la tristezza splende ancora,

E la ruggine ricorda ancora.

Coro (crescendo, voci spezzate):

Il sacrificio non guarisce.

La memoria non guarisce.

Ma dobbiamo cantare.

(Il gufo gracchia. Il sipario ondeggia e i viandanti avanzano in silenzio.)

Coro finale (multilingue, spezzato, echeggiante):

Esse quam videri.

Non essere un’apparenza, ma un essere. La presenza trascende l’illusione.

Ry Tanindrazanay – Amata Terra,

Veninia – Benedetta Tenerezza,

Onde, ferite, un nuovo inizio.

(Le luci si spengono. Silenzio. Solo il sussurro degli aghi di pino.)

Preghiera

Giapponese (preghiera shintoista):

Okuninushi-no-Mikoto,

Abbraccia il mio corpo malato,

Signore del mondo nascosto,

Dà guarigione al silenzio.

Latino (sacro):

Magister Terrarum Magnus,

Vulnera nostra amplectere.

Dominus Mundi Occulti,

da pacem et sanitatem in silentio.

Greco (liturgico, omerico):

Ὦ Δεσπότα Μεγάλων Χθονίων,

πληγάς ἡμετέρας περίλαβε·

Κύριε τοῦ Κεκρυμμένου Κόσμου,

δὸς εἰρήνην καὶ ἴασιν ἐν σιγῇ.

Etrusco (tono rituale ristrutturato):

Aplù Larth Velχan,

Thurunsva θu,

cilθ meθlum,

śanś tenθur śec.

(Signore degli Inferi, abbraccia la mia carne ferita, e sovrano del mondo nascosto, concedimi la guarigione del silenzio.)

Spirale (fili intrecciati)

Okuninushi-no-Magi — Magister Terrarum — Δεσπότα Χθονίων — Larth Velχan,

Corpo malato — vulnera nostra — πληγάς ἡμετέρας — cilθ meθlum.

Signore del Mondo Nascosto — Dominus Mundi Occulti — Κύριε τοῦ Κεκρυμμένου Κόσμου — thurunsva θu,

Silenzio — silentium — σιγή — śec.

Guarigione — sanitatem — ἴασιν — tenθur.

Perdono — pacem — εἰρήνην — śanś.

Quattro lingue si mescolano,

come le basi di una doppia elica:

A (abbracciando),

T (Dio),

C (Dio),

G (creatore).

Okuninushi-no-Mikoto

Latino:

Fito: germe occultae medicinae,

(Fito: seme nascosto della guarigione)

emanazione Ōkuninushi,

(Manifestazione di Okuninushi,)

qui vulnera radices facis,

(Colui che trasforma le ferite in radici,)

qui febrem flumen vitae mutas,

(Colui che trasforma la febbre in un fiume di vita,)

veni, sanare in silentio.

(Vieni e guarisci in silenzio.)

Giapponese:

Fito,

(Fito,)

Sorgente del respiro di Okuninushi-no-Mikoto,

(Primavera del respiro di Okuninushi,)

Abbraccia il mio corpo malato,

(Abbraccia il mio corpo malato,)

Dona guarigione in silenzio.

(Concedi guarigione al silenzio.)

Greco:

Bene, βλάστημα κεκρυμμένης ἰάσεως,

(O Fito, germoglio nascosto di guarigione,)

ὃς τὸν πυρετὸν ποταμὸν ζωῆς ποιεῖς,

(Tu che trasformi la febbre in un fiume di vita,)

παρεῖναι, ἰᾶσθαι.

(Sii qui e guarisci.)

Etrusco:

Fito, sprona θu,

(O Fito, germoglio sacro,)

śec θana,

(Dà silenzio,)

śanś tur.

(Porta pace.)

Book IV / Ouverture

(low electrical hum; flicker of neon; wind in pines)

Voice One (broken, tired):

River burning — kidneys heavy — spores chant.

Fever bends time.

I am walking the wound.

Chorus (layered tongues):

No demons, only hands.

Pas de diables, que des mains.

(a match strike, fragile flame)

The Little Match Girl (child, almost singing):

Each flame is mother.

Each flame is chapel.

Each flame is gone.

Soviet Babushka (dry cough, whisper):

We sell fire to eat.

We eat smoke to live.

We live memory to die.

Chorus (thin, splintered):

Every match a cosmos.

Every death untranslatable.

(bass hum, underwater, like distant thunder)

Cthulhu (submerged, rumbling):

— wave inside wave —

— trauma tide —

— not separate —

(silence. faint sound of shrine bells. wooden clappers.)

Kami Voice (gentle, interrupting):

Even the fever is kami.

Even the matchstick is shrine.

Bow to the spore —

it has its reason.

(pause. then the calm voice of Jung.)

Jung (resurrected, steady):

Synchronicity is not trick,

but conversation —

world and psyche

meeting without appointment.

Twin Peaks is valley,

archetype reflected in static.

(a child’s German voice, faint, echoing through trees.)

Momo:

„Ich höre die Zeit,

wenn ihr sie verliert.“

(I hear time

when you lose it.)

Chorus (liturgical layering):

Kyrie eleison — رحمنا يا رب — Om mani padme hum —

Ry Tanindrazanay malala ô.

(metallic rust, voice trembling, The Happy Prince.)

Happy Prince:

I gave my gold, my eyes,

and the city forgot.

Still sorrow gleams.

Still rust remembers.

Chorus (crescendo, fractured):

Sacrifice does not cure.

Memory does not heal.

Yet both must be sung.

(owl call. curtains sway. wanderers step forward, silent.)

Final Choral Weave (multi-lingual, broken, echoing):

Esse quam videri.

To be — not to seem.

存在は幻を超えて.

Ry Tanindrazanay — beloved land,

Benignia — blessed kindness,

wave, wound, beginning again.

(lights cut. silence, except pine-needles whispering.)

Prologue (Haiku, post-Ouverture)

I

千年杉

沈黙の中に

声は生きる

(Thousand-year cedar —

within the silence

voices still live.)

II

熱の川

仲間と渡り

死に近づく

(River of fever —

crossed with companions,

drawn near to death.)

III

痴呆の門

目を合わせつつ

息を分ける

(Gate of dementia —

meeting only with eyes,

sharing the breath.)

—

Chapter I

IV

spur θu, — sacred sprout,

sepsis and shadow root,

clay-urns of ancestors whisper.

V

śec θana, — give silence,

fever bends the red soil,

mortality traced in veins of stone.

VI

śanś tur, — bring peace,

dementia’s unbound tongue

returns to the oak-groves.

VII

Volterra wind howls:

no hero survives,

only the archive of pain and bond.

—

VIII

In Carnunto, sub Pannoniae caelo,

faces morborum ardebant.

Stetit imperator, sed corpus frangebatur.

In Carnuntum, under the Pannonian sky,

the torches of sickness burned.

The emperor stood, but his body was breaking.

—

IX

Mors non est malum,

sed natura resolvens.

Sic flumina aquarum, sic folia autumni.

Death is no evil,

but nature unbinding.

So flow the rivers, so fall the autumn leaves.

—

X

Memini me hominem,

non dominum vitae.

Et in febre didici:

omnes sumus fratres in exitu.

I remember I am a man,

not master of life.

And in fever I learned:

we are all brothers in departing.

—

XI

Λάβρυος λιμήν,

ἄνεμοι μινωίαι,

θάνατος ἐν ψιθύροις.

Labrys harbour,

Minoan winds,

death among whispers.

XII

Κρίνα ἀνθέουσι,

παγώνιον ἀλαλάζει·

οὐ βασιλεὺς Μίνως,

ἀλλ’ ἄνθρωποι βήχοντες.

Lilies bloom,

a peacock cries;

not king Minos,

but coughing wanderers.

XIII

Μέλαινα αἴλουρος

σκιὰν ἀναβαίνει,

ὑπὸ γαλήνην θαλάσσης.

A black cat

climbs through shadow,

under the calm of the sea.

To be continued…

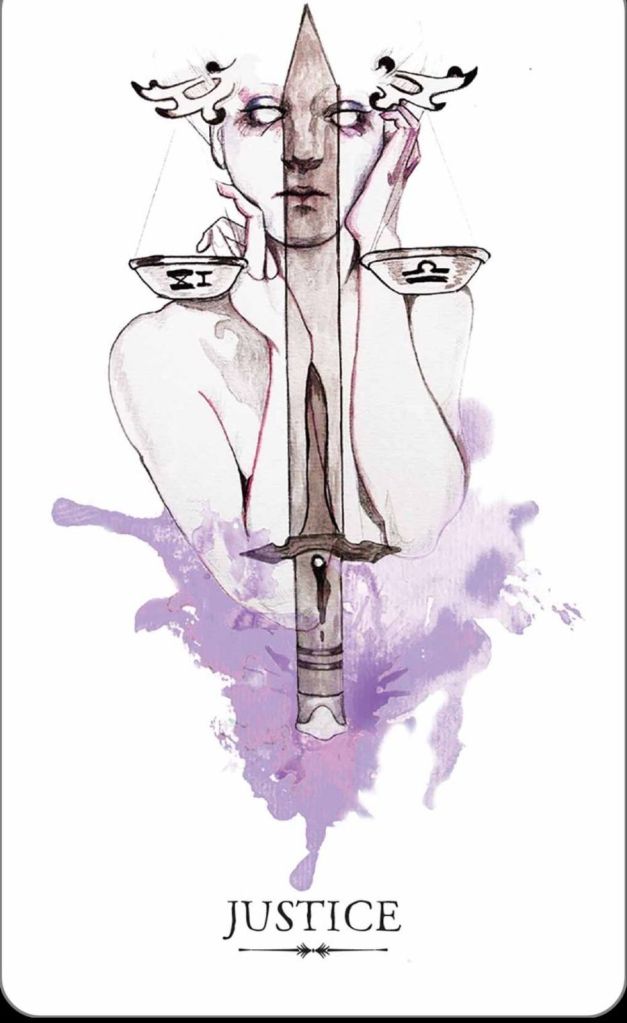

Justice

Scene: Pharmakon

In medias res

(A half-lit stage. On one side, a stone courtyard tangled with vines; swine rustle at the edges. On the other, a faint shimmer of spice-laden air, the outline of a shape-shifter flickering. Circe and Scytale face one another across a circle of silence. A mortar and pestle rest on the ground; Scytale’s flesh shifts subtly as he speaks.)

CIRCE

(pressing leaves into stone)

You carry your poison in your skin.

I grind mine from roots.

Which of us is truer?

SCYTALE

(smiling blandly, face rippling)

Truth is a face the moment before it changes.

“Our hostilities are better left unvoiced.”

CIRCE

(gestures toward the swine)

Unvoiced?

See them. They squeal what men dare not speak.

The potion tore away their words,

left only hunger.

SCYTALE

(laughs softly, voice a wheeze)

And yet hunger is honest.

Faces lie more sweetly than squeals.

I am no less healer than you.

I give them new masks to survive their wars.

CIRCE

(snarls, then softens)

Survive?

Or vanish?

The pharmakon does not spare—it unmasks.

Poison and cure—

two sips of the same cup.

SCYTALE

(nods, his form shifting to mirror Circe’s own face)

Exactly.

Look—yourself.

Do you know whether this reflection

is venom

or salvation?

CIRCE

(stares at her double, voice low)

I know only this:

whatever you wear, whatever I brew,

the beast is waiting.

In you, in me, in all.

SCYTALE

(steps into the half-dark, voice echoing)

Then perhaps, sorceress,

we are the same draught—

two halves of one unspoken dose.

(Silence. The swine grunt and stir. The leaves drip bitter sap into the dust. The air ripples as if with spice. Both figures hold still, caught between cure and poison.)

BLACKOUT.

Κίρκη

ΦΑΡΜΑΚΟΝ

Sourceress speaks

ἔνθ’ ἄρα Κίρκη—

I crush the leaf—

potens herbis—

the stone remembers—

ἄνδρας δ’ ἐφύβρισεν—

miscet et arte nocentem—

bitter sap runs,

venenum fit medicina,

εἰς σῦας—

sharp as frost, clean as salt—

Ὀδυσσεὺς δ’ ἔσχε μῶλυν,

idem exitium, idem remedium,

Drink it, and see—

ἀντίκαρ φαρμάκου φάρμακον—

the beast beneath your skin,

quae dat, ipsa rapit—

the root in your blood.

Too much—ἔνθ’ ἄρα Κίρκη—

and the earth tilts,

venenum—medicine—ruin—

Just enough, and the wound closes.

Every green thing—

εἰς σῦας—

is double.

Child of sun,

atque eadem vires—

child of soil.

My hand offers both,

moly against moly,

venenum fit medicina—

My cup is danger.

φάρμακον, φάρμακον—

My cup is grace.

Endgame: The Belly and the Valve

Courtesy of Bran Mak Muffin

[Scene: The Kitchen of CristopheroColombia. The stoves are cold, the cupboards gutted. Smoke rises where history has already burned. Two figures remain: El Presidente, un bad hombre, belly distended and glistening; and Regal Anal, immaculate, tight, smiling like a sphincter. They sit across from one another, surrounded by ashes.]

El Presidente (The Belly):

I have eaten the people, the factories, the children. My stomach is swollen with their applause. And yet I am still hungry.

Regal Anal (The Valve):

You mistake expulsion for power. True sovereignty is not to swallow, but to withhold. I held the nation in my smile, clenched and gleaming. Nothing escaped.

The Belly:

Your smile was constipation. A blockage dressed in cinema. I am the open mouth, the endless feast. I take in all — and so I am the world.

The Valve:

And what remains after you devour it? Only waste, chaos, indigestion. You are a sewer, not a sovereign. I produce order, little pellets of meaning, clean and shaped for the cameras.

The Belly (patting himself, burping ink):

Better to choke on the world than to chew on my words.

The Valve (adjusting his grin):

Better to polish excrement into slogans than to drown in bile.

[A silence. Smoke drifts. The Great McCarthy-zeppelin groans above, casting no shade.]

The Belly:

We are endgame, you and I. Appetite and retention. Mouth and sphincter.

The Valve:

Yes. Between us, the nation is consumed and excreted. Nothing left but the smell.

The Belly:

Then let us toast. To hunger.

The Valve:

To control.

[They raise goblets of molten rhetoric. Offstage, a faint insect-chitter echoes — the last workers scratching at the tiles of the kitchen. The lights buzz, flicker, and fail. Curtain.]

The Belly of the President: Part II

Appetizer: The Workers

In the kitchen of CristopheroColombia, the stoves glowed with a bureaucratic heat, and the cupboards rattled with paper. Here, El Presidente — un bad hombre — waddled in, belly-first, the same belly that once, in the Disunited Frames, had turned itself belly-up like a Kafka beetle.

But now his metamorphosis had deepened: no longer merely grotesque in form, he had become a gluttonous priest of bureaucracy, preparing to consume his people as if they were the nation’s natural hors d’oeuvres.

The workers arrived not as citizens but as creatures. Kafka would have recognized them: clerks with thoraxes, teachers with antennae, nurses crawling with the long legs of cockroaches. Each carried on its carapace a stamped decree: permit approved, loan denied, case closed. The very ink of bureaucracy had become their shell.

The fluorescent lights buzzed like a chorus of typewriters. The swarm scuttled in crooked lines, their antennae twitching to the rhythm of rubber stamps. They did not sing protest songs, but the monotonous hum of waiting rooms and government offices.

“¡Maravilloso!” bellowed El Presidente, un bad hombre, his voice greasy with delight. “At last, the hors d’oeuvres arrive pre-packaged — portioned and numbered! Innovation made flesh!” He lifted his golden fork, a trident hammered out of campaign promises, and plunged it into the swarm.

He chewed loudly, bones and wings snapping like brittle constitutions. Ink smeared his lips, the bureaucratic sauce of the nation.

Each bite erased an institution:

a factory dissolved into sludge in his stomach,

a school shriveled like paper in a furnace,

a hospital burst like a blister on his tongue.

He belched, and the air filled with the smell of disinfectant, despair, and broken ballots. “Delicious,” he declared, patting his legendary belly. “Such innovation in suffering! Such efficiency in sacrifice!”

The swarm, compelled by invisible decrees lodged in their thoraxes, crawled forward into his maw. They clicked their mandibles in unison, as if chanting: Better to be consumed than forgotten.

And high above, drifting like a bloated omen, the Great McCarthy-zeppelin hovered. Its sagging bulk cast no shade, only suspicion, while El Presidente raised a goblet of molten rhetoric and toasted his own appetite.

“Workers are but snacks,” he declared, stomach rumbling like a parliament in ruins. “Bring me the main course! Bring me the children!”

MAKE AMERICA SICK AGAIN

The Belly of the President

(English, Spanish, Cherokee, Cheyenne, Russian, Korean)

English

In the Disunited Frames, there dwelt a President so swollen with appetite that even Pantagruel, that monarch of monstrous gullets, might have whispered, “Sir, your hunger is unseemly.” For the President desired not mere banquets of beef or pie, but whole companies — morsels of machinery and chips, fried and salted and called “innovation.”

Upon a restless dawn, he awoke and found himself overturned, belly-up, his limbs twitching like a Kafka beetle. “Oh wondrous transformation!” he cried. “I am reborn a communist — a lover of Mr. Tin Poo, who keeps his treasure locked in porcelain, and a humble student of the glorious Mr. Young Kim, whose every statue looks like my mirror.”

He strutted about in confusion, rehearsing decrees to invisible ministers, when lo! his sidekick, Mr. Cohen, appeared. This Cohen was no ordinary counselor but an apparition, dressed in the robes of the American Lawyer’s Bar, muttering oaths to the Great McCarthy — that zeppelin of suspicion floating still above the clouds, promising shade to none and fear to all.

“Tell me, Cohen,” the President begged, “if I buy up every microscopic company, will I not thereby own the world?”

“Indeed, Sire,” said the ghostly lawyer. “But be careful not to swallow yourself.”

Yet the President, drunk on his own echo, replied: “Better to choke on the world than to chew on my words!” And so he marched forth, belly first, toward the kitchen of history — a kitchen already ablaze.

Español

En los Marcos Desunidos vivía un Presidente tan hinchado de apetito que hasta Pantagruel, aquel monarca de las gargantas monstruosas, habría susurrado: “Señor, su hambre es indecorosa.” Pues el Presidente deseaba no banquetes de carne o pastel, sino empresas enteras — bocados de maquinaria y chips, fritos y salados, bautizados “innovación.”

Al amanecer de un día inquieto, despertó y se encontró volcado, panza arriba, sus miembros retorciéndose como un insecto kafkiano. “¡Oh, maravillosa transformación!”, gritó. “He renacido comunista — amante del señor Lata Pú, que guarda su tesoro en porcelana, y humilde discípulo del glorioso señor Joven Kim, cuyas estatuas son como espejos de mi rostro.”

Deambulaba confundido, ensayando decretos para ministros invisibles, cuando ¡he aquí! apareció su escudero, el señor Cohen. Este Cohen no era consejero ordinario sino aparición, vestido con las togas del Colegio de Abogados de América, murmurando juramentos al Gran McCarthy — aquel dirigible de sospecha que aún flota en las nubes, prometiendo sombra a ninguno y miedo a todos.

“Dime, Cohen,” rogó el Presidente, “si compro cada empresa microscópica, ¿no poseeré así el mundo entero?”

“En efecto, Sire,” respondió el espectral abogado. “Pero tenga cuidado de no tragarse a sí mismo.”

Y sin embargo, ebrio de su propio eco, replicó el Presidente: “¡Mejor atragantarme con el mundo que masticar mis palabras!” Y así marchó, vientre por delante, hacia la cocina de la historia — una cocina ya en llamas.

Cherokee (ᏣᎳᎩ) – Approximate Draft

(Note: This is an imperfect, symbolic rendering. Cherokee is polysynthetic and endangered, with few fluent speakers. This draft uses dictionary-based words and simplified constructions. A fluent speaker should refine it. It is offered as a gesture of respect.)

ᎤᏍᏆᏂᎪᎯ ᏧᏣᏂᏱ ᏧᏍᏆᎦᏟ ᎠᏆᏛᏍᎩ ᎤᏍᎦᏚᎩ ᏂᎦᏓᏘ ᎤᏓᏔᎲᎢ.

ᏧᎦᏃᏮᏛᏗ Pantagruel ᎠᎦᏔᎲᎢ, ᏂᎦᏓᏘ ᎠᏓᏆᏛᏍᎩ, ᎤᏍᎦᏚᎩ ᎤᏍᎩᎦᏟ: “ᎤᏍᏆᎦᎾᎯ, ᎠᏆᏛᏍᎩ ᎠᎦᏔᎲᎢ.”

ᏧᏍᏆᎦᏟ ᎠᎦᏔᎲᎢ ᎤᏓᏔᎲᎢ ᎠᎦᏔᎲᎢ ᎠᎩᏍᏛ ᎤᏓᏆᏛᏍᎩ ᎠᎦᏔᎲᎢ Kafka ᏧᏓᏆᏛᏍᎩ ᎠᏥᏍᏆᎦᎵ.

ᎤᏍᎦᏚᎩ: “ᏙᎯᎠ! ᏧᏣᎪᏪᎵᏍᏗ ᎠᏆᏛᏍᎩ.”

ᏧᎦᏃᏮᏛᏗ Tin Poo, ᎠᎦᏔᎲᎢ ᎠᏆᏛᏍᎩ.

ᏧᎦᏃᏮᏛᏗ Young Kim, ᎠᏆᏛᏍᎩ ᎤᎦᏃᏮᏛᏗ.

ᎤᏩᏒᏍᏔᏅᎢ Cohen ᏧᏓᏆᏛᏍᎩ. ᏧᎦᏃᏮᏛᏗ ᎤᏂᎩᏍᏛ ᎠᎦᏔᎲᎢ ᎠᏆᏛᏍᎩ.

ᏧᎦᏃᏮᏛᏗ McCarthy, ᏗᎦᏓᏘ ᎠᏆᏛᏍᎩ ᏗᏓᎾᏕᏲᎲᎢ.

“ᎦᏙᎯ, Cohen,” ᎠᏆᏛᏍᎩ ᎤᏍᎦᏚᎩ,

“ᎤᏍᏆᎦᏟ ᎠᏓᎾᏕᏲᎲᎢ ᏧᎦᏃᏮᏛᏗ ᎤᏍᎦᏚᎩ?”

Cohen ᎤᏍᎦᏚᎩ: “ᎤᏍᎦᏚᎩ, ᎠᏆᏛᏍᎩ. ᎦᏙᎯ ᎤᎩᏍᏛ ᎤᏍᎦᏚᎩ.”

ᎠᏆᏛᏍᎩ ᎤᏍᎦᏚᎩ: “ᎤᏍᎦᏚᎩ ᏧᎦᏃᏮᏛᏗ ᎤᏍᎦᏚᎩ ᏧᏓᏆᏛᏍᎩ!”

ᎤᏍᎦᏚᎩ ᎠᏆᏛᏍᎩ ᎠᎦᏔᎲᎢ, ᏧᎦᏃᏮᏛᏗ ᏧᏍᏆᎦᏟ ᎤᏍᎦᏚᎩ.

Cheyenne (Tsėhesenėstsestȯtse) – Approximate Draft

(Note: Imperfect symbolic rendering, based on dictionaries and simplified grammar. Fluency requires a native speaker. Offered with respect.)

Náévȯhómevéséhe Disunited Frames náhkohe éhóxeheho.

Náhkohe óho’eno, náxháevestȯtse ho’éénohe, neháve’ame Pantagruel ésevȯhóme:

“He’ehnéhe, néváá’e, ného’ȯxe náho’éstséstse.”

Náhkohe ho’xėhéóhe, náhóxe héstó’e, ho’ȯhóne Kafka beetle.

“Náohtséhe!” ného’ȯxe. “Náohtséhe communist. Náohtséhe Tin Poo. Náohtséhe Young Kim.”

Náhkohe néxhae ministers óhkėstse invisible.

Náóhtse Cohen, apparition, American Lawyer.

Náóhtse McCarthy, zeppelin suspicion.

“Náheve, Cohen,” ného’ȯxe náhkohe,

“náhkȯhe ohke ne’stse companies, náhkȯhe earth?”

“Ehne’ėstse,” ného’ȯxe Cohen.

“He’ehnéhe, néváá’e, néma’ėstse néméhovȯhého.”

Náhkohe: “Better choke earth than chew words!”

Náhkohe vóehéno kitchen history — náóhkėstse ablaze.

Русский (Russian)

В Разъединённых Рамках жил Президент, настолько распухший от аппетита, что даже Пантагрюэль, монарх чудовищных желудков, прошептал бы: «Сэр, ваш голод неприличен». Президент желал не просто пиров из говядины или пирогов, но целые компании — куски машин и чипсов, жареные, солёные и называемые «инновацией».

На беспокойном рассвете он проснулся и обнаружил себя перевёрнутым, брюхом вверх, дёргающим конечностями, словно жук Кафки. «О, чудесное превращение!» — вскричал он. «Я возрожден как коммунист — любитель господина Жестяной Банки, который хранит сокровище в фарфоре, и скромный ученик славного господина Юного Кима, каждая статуя которого — моё зеркало».

Он вышагивал в смятении, репетируя указы невидимым министрам, и вот! появился его напарник, господин Коэн. Этот Коэн был не обычным советником, а призраком, облачённым в мантии Американской коллегии адвокатов, бормочущим клятвы Великому Маккарти — тому дирижаблю подозрения, всё ещё парящему над облаками, обещающему никому не тень, а всем — страх.

«Скажи мне, Коэн, — умолял Президент, — если я скуплю каждую микроскопическую компанию, не станет ли весь мир моим?»

«Да, господин, — ответил призрачный юрист. — Но будьте осторожны, чтобы не проглотить самого себя».

Но Президент, опьянённый собственным эхом, воскликнул: «Лучше подавиться миром, чем жевать свои слова!» И он отправился, живот вперёд, в кухню истории — кухню, уже охваченную пламенем.

—

한국어 (Korean)

분열된 틀의 나라에 한 대통령이 살고 있었다. 그는 식욕으로 너무나 부풀어 올라, 괴물 같은 위장의 군주 팡타그뤼엘조차 속삭였을 것이다. “각하, 당신의 굶주림은 추하다.” 대통령은 소고기 잔치나 파이 따위가 아니라, 전체 회사를 원했다 — 기계와 칩의 조각들, 기름에 튀겨지고 소금에 절여져 “혁신”이라 불리는 것들.

불안한 새벽, 그는 깨어나 보니 몸이 뒤집혀 배를 위로 드러낸 채, 팔다리가 카프카의 곤충처럼 꿈틀거리고 있었다. “오, 놀라운 변신이여!” 그가 외쳤다. “나는 공산주의자로 다시 태어났다 — 자기 보물을 도자기에 감춘 틴 푸 씨의 연인, 그리고 모든 동상이 내 얼굴을 비추는 영광스러운 김 군의 겸손한 제자!”

그는 혼란 속에 거닐며, 보이지 않는 장관들에게 포고령을 리허설하고 있었다. 바로 그때! 그의 곁에는 보좌관 코헨 씨가 나타났다. 이 코헨은 평범한 참모가 아니라 환영이었다. 미국 변호사 협회의 예복을 입고, 위대한 매카시에게 맹세를 중얼거렸다 — 아직도 구름 위를 떠다니며, 그 누구에게도 그늘을 주지 않고 모두에게 두려움만을 주는 의심의 비행선.

“코헨, 말해보라,” 대통령이 애원했다. “내가 모든 미시적인 회사를 사들인다면, 세상은 내 것이 되지 않겠는가?”

“그렇습니다, 각하,” 유령 같은 변호사가 대답했다. “그러나 스스로를 삼키지 않도록 조심하십시오.”

그러나 대통령은 자기 메아리에 취해 외쳤다. “세상을 삼켜 질식하는 것이 내 말을 씹는 것보다 낫다!” 그리고 그는 배를 내밀고 역사라는 부엌으로 행진했다 — 이미 불타고 있는 부엌으로.

Reader’s Note (Cherokee and Cheyenne version): This translation is symbolic and approximate. Cherokee (ᏣᎳᎩ) is a polysynthetic and endangered language; fluent speakers should refine it. This draft is offered with respect for the Cherokee and Cheyenne people and their language.

私は祖父に、それはただの夢だったのかと尋ねました。祖父はそうだと答えました。

彼らは私たちの心を暗い毛布の下に包み込んだ

小さな真夜中の月の下、私たちは恐れることなく眠った

彼は20歳の将軍だった

青い瞳とおそろいのジャケット

彼は20歳の将軍だった

嵐の子

サンドクリークの底に銀貨がある

私たちの戦士たちはバッファローの道を遠くへ

そして遠くの音楽はますます大きくなった

私は三度目を閉じた

私は再びそこにいた

祖父に、これはただの夢なのかと尋ねた

祖父はそうだと答えた

時々、サンドクリークの底で魚が歌う

うん

夢を見すぎて鼻血が出た

片方の耳には稲妻、もう片方の耳には楽園

小さな涙

大きな涙

スノーツリーが

赤い星で咲いたとき

今、子供たちはサンドクリークのベッドで眠っている

うん

うん

太陽が夜の肩の間から頭を上げたとき

そこには犬と煙と逆さまのテントしかなかった

私は空に矢を放った

息をさせろ

風に向かって矢を放った

血を流させるために

サンド・クリークの底で3本目の矢を探せ

うん

うん

奴らは俺たちの心を暗い毛布の下に包み込んだ

小さな死月の下、俺たちは恐れることなく眠った

彼は20歳の将軍だった

ターコイズブルーの瞳とそれに合うジャケット

彼は20歳の将軍だった

嵐の子

今、子供たちはサンド・クリークの底で眠っている

うん

うん

もう一度の回転

真実を知るすべての子供たちへ

もう一度の回転

第四巻/序曲

(低い電気の唸り;ネオンの明滅;松林を抜ける風)

第一の声(壊れ、疲れた声):

燃える川 ― 重くのしかかる腎臓 ― 胞子の詠唱。

熱は時間を曲げる。

私は傷を歩いている。

合唱(重層の舌):

悪魔ではない、ただの手だ。

悪魔ではなく、ただの手。

(マッチが擦られ、かすかな炎が灯る)

マッチ売りの少女(子どもの声、歌うように):

ひとつの炎は母。

ひとつの炎は礼拝堂。

ひとつの炎は消え去る。

ソビエトのバーブシュカ(咳混じりの囁き):

火を売って食べ、

煙を食べて生き、

記憶を生きて死ぬ。

合唱(薄く、裂けた声):

すべてのマッチは宇宙。

すべての死は翻訳不能。

(低音の唸り、水底から、遠雷のように)

クトゥルフ(沈んだ声、地鳴りのように):

― 波の中に波 ―

― 外傷の潮 ―

― 分かたれてはいない ―

(沈黙。神社の鈴のかすかな音。拍子木。)

神の声(やさしく、割り込む):

熱さえも神。

マッチ棒さえも社。

胞子に頭を垂れよ ―

それにも理がある。

(間。ユングの落ち着いた声が続く。)

ユング(甦り、静かに):

共時性は欺きではなく、

対話だ ―

世界と魂が、約束なく出会う。

ツインピークスは谷、

原型は雑音に映る。

(木立の中から反響する、ドイツ語の子どもの声)

モモ:

「君たちが時間を失うとき、

私はその時間を聴く。」

合唱(典礼的な層):

Kyrie eleison ― رحمنا يا رب ― Om mani padme hum ― Ry Tanindrazanay malala ô.

(金属の錆のような声、震える、幸福な王子)

幸福な王子:

私は黄金も、瞳も捧げた。

そして街は忘れた。

それでも悲しみは輝き、

それでも錆は覚えている。

合唱(クレッシェンド、砕けた声):

犠牲は癒さない。

記憶は治さない。

それでも、歌わねばならぬ。

(梟の声。幕が揺れ、放浪者たちが無言で進み出る。)

最終合唱織り(多言語、壊れ、反響して):

Esse quam videri.

見せかけではなく、存在であれ。

存在は幻を超えて。

Ry Tanindrazanay ― 愛しき大地、

ベニーニア ― 祝福された優しさ、

波、傷、再びの始まり。

(灯りが落ちる。沈黙。ただ松の葉のささやき。)

祈願

日本語(神道の祈り):

大国主神よ、

病める身を抱きしめ、

隠れ世の主よ、

静けさに癒しを授け給え。

ラテン語(聖礼的):

Magister Terrarum Magnus,

vulnera nostra amplectere.

Dominus Mundi Occulti,

da pacem et sanitatem in silentio.

ギリシア語(典礼的、ホメロス風):

Ὦ Δεσπότα Μεγάλων Χθονίων,

πληγάς ἡμετέρας περίλαβε·

Κύριε τοῦ Κεκρυμμένου Κόσμου,

δὸς εἰρήνην καὶ ἴασιν ἐν σιγῇ.

エトルリア語(再構された儀礼調):

Aplu Larth Velχan,

thurunsva θu,

cilθ meθlum,

śanś tenθur śec.

(地下の主よ、傷ついた肉を抱きしめ、隠された世界の支配者よ、沈黙の癒しを授け給え。)

螺旋(交錯する糸)

大国主神 — Magister Terrarum — Δεσπότα Χθονίων — Larth Velχan,

病みし身 — vulnera nostra — πληγάς ἡμετέρας — cilθ meθlum.

隠れ世の主 — Dominus Mundi Occulti — Κύριε τοῦ Κεκρυμμένου Κόσμου — thurunsva θu,

静けさ — silentium — σιγή — śec.

癒し — sanitatem — ἴασιν — tenθur.

赦し — pacem — εἰρήνην — śanś.

四つの舌が交わり、

二重螺旋の塩基のように:

A(抱擁)、

T(神)、

C(神)、

G(生み手)。

大国主命/オオクニヌシノミコト

ラテン語:

Fito — germen occultae medicinae,

(フィト ― 隠された癒しの種子、)

emanatio Ōkuninushi,

(オオクニヌシの発露、)

qui vulnera radices facis,

(傷を根に変える者、)

qui febrem flumen vitae mutas,

(熱を命の川に変える者、)

veni, sanare in silentio.

(来たりて、沈黙のうちに癒せ。)

日本語:

フィトよ、

(フィトよ、)

大国主神の息吹の芽、

(オオクニヌシの息吹の芽よ、)

病みし身を抱き、

(病める身を抱きしめ、)

静けさに癒しを授け給え。

(静けさに癒しを授け給え。)

ギリシア語:

Φῖτο, βλάστημα κεκρυμμένης ἰάσεως,

(フィトよ、隠された癒しの芽よ、)

ὃς τὸν πυρετὸν ποταμὸν ζωῆς ποιεῖς,

(熱を命の川に変える者よ、)

παρεῖναι, ἰᾶσθαι.

(ここに在りて、癒せ。)

エトルリア語:

Fito, spur θu,

(フィトよ、聖なる芽よ、)

śec θana,

(静けさを与え、)

śanś tur.

(平和をもたらせ。)

Un altro giro

Libro IV / Ouverture

(Basso ronzio di elettricità; luci al neon tremolanti; vento attraverso la pineta)

Prima voce (voce rotta e stanca):

Fiume ardente – reni pesanti – il canto delle spore.

La febbre piega il tempo.

Cammino attraverso le ferite.

Coro (lingue stratificate):

Non un diavolo, solo una mano.

Non un diavolo, solo una mano.

(Si accende un fiammifero, si accende una debole fiamma.)

La piccola fiammiferaia (voce infantile, cantando):

Una fiamma è una madre.

Una fiamma è una cappella.

Una fiamma si spegne.

Babushka sovietica (tossendo, sussurrando):

Vendi fuoco e mangia,

Vivi fumo e vivi memoria e muori.

Coro (voce sottile e rotta):

Ogni fiammifero è un universo.

Ogni morte è intraducibile.

(Un basso rombo, dalle profondità dell’oceano, come un tuono lontano)

Cthulhu (una voce sommessa, come un terremoto):

- Onda dentro onda –

- Maree di traumi –

- Non divisi –

(Silenzio. Il debole suono di una campana di un santuario. Batti di legno.)

Voce di Dio (interrompendo dolcemente):

Anche il calore è un dio.

Anche un fiammifero è un santuario.

Inchinatevi alle spore –

C’è una ragione per questo.

(Pausa. La voce calma di Jung continua.)

Jung (rinvigorito, a bassa voce):

La sincronicità non è un inganno,

è un dialogo –

Mondo e anima si incontrano senza promessa.

Twin Peaks sono una valle,

gli archetipi si riflettono nel rumore.

(Voci di bambini echeggiano dagli alberi, parlando in tedesco.)

Momo:

“Quando perdi tempo,

io lo ascolto.”

Coro (strato liturgico):

Kyrie eleison – Rāṇḍābhi yāṇḍābhi – Om mani padme hum – Ry Tanindrazanay malala ô.

(Il Principe Felice, voce come metallo arrugginito, tremante)

Principe Felice:

Ho offerto il mio oro e i miei occhi.

E la città ha dimenticato.

Ma la tristezza splende ancora,

E la ruggine ricorda ancora.

Coro (crescendo, voci spezzate):

Il sacrificio non guarisce.

La memoria non guarisce.

Ma dobbiamo cantare.

(Il gufo gracchia. Il sipario ondeggia e i viandanti avanzano in silenzio.)

Coro finale (multilingue, spezzato, echeggiante):

Esse quam videri.

Non essere un’apparenza, ma un essere. La presenza trascende l’illusione.

Ry Tanindrazanay – Amata Terra,

Veninia – Benedetta Tenerezza,

Onde, ferite, un nuovo inizio.

(Le luci si spengono. Silenzio. Solo il sussurro degli aghi di pino.)

Preghiera

Giapponese (preghiera shintoista):

Okuninushi-no-Mikoto,

Abbraccia il mio corpo malato,

Signore del mondo nascosto,

Dà guarigione al silenzio.

Latino (sacro):

Magister Terrarum Magnus,

Vulnera nostra amplectere.

Dominus Mundi Occulti,

da pacem et sanitatem in silentio.

Greco (liturgico, omerico):

Ὦ Δεσπότα Μεγάλων Χθονίων,

πληγάς ἡμετέρας περίλαβε·

Κύριε τοῦ Κεκρυμμένου Κόσμου,

δὸς εἰρήνην καὶ ἴασιν ἐν σιγῇ.

Etrusco (tono rituale ristrutturato):

Aplù Larth Velχan,

Thurunsva θu,

cilθ meθlum,

śanś tenθur śec.

(Signore degli Inferi, abbraccia la mia carne ferita, e sovrano del mondo nascosto, concedimi la guarigione del silenzio.)

Spirale (fili intrecciati)

Okuninushi-no-Magi — Magister Terrarum — Δεσπότα Χθονίων — Larth Velχan,

Corpo malato — vulnera nostra — πληγάς ἡμετέρας — cilθ meθlum.

Signore del Mondo Nascosto — Dominus Mundi Occulti — Κύριε τοῦ Κεκρυμμένου Κόσμου — thurunsva θu,

Silenzio — silentium — σιγή — śec.

Guarigione — sanitatem — ἴασιν — tenθur.

Perdono — pacem — εἰρήνην — śanś.

Quattro lingue si mescolano,

come le basi di una doppia elica:

A (abbracciando),

T (Dio),

C (Dio),

G (creatore).

Okuninushi-no-Mikoto

Latino:

Fito: germe occultae medicinae,

(Fito: seme nascosto della guarigione)

emanazione Ōkuninushi,

(Manifestazione di Okuninushi,)

qui vulnera radices facis,

(Colui che trasforma le ferite in radici,)

qui febrem flumen vitae mutas,

(Colui che trasforma la febbre in un fiume di vita,)

veni, sanare in silentio.

(Vieni e guarisci in silenzio.)

Giapponese:

Fito,

(Fito,)

Sorgente del respiro di Okuninushi-no-Mikoto,

(Primavera del respiro di Okuninushi,)

Abbraccia il mio corpo malato,

(Abbraccia il mio corpo malato,)

Dona guarigione in silenzio.

(Concedi guarigione al silenzio.)

Greco:

Bene, βλάστημα κεκρυμμένης ἰάσεως,

(O Fito, germoglio nascosto di guarigione,)

ὃς τὸν πυρετὸν ποταμὸν ζωῆς ποιεῖς,

(Tu che trasformi la febbre in un fiume di vita,)

παρεῖναι, ἰᾶσθαι.

(Sii qui e guarisci.)

Etrusco:

Fito, sprona θu,

(O Fito, germoglio sacro,)

śec θana,

(Dà silenzio,)

śanś tur.

(Porta pace.)