Magna, October

It always starts with rain.

Not the cinematic kind — the dull northern kind that seeps through everything, soft, unending, democratic.

By the third week of the Magna excavation, I stopped noticing when I was wet.

Mud had become another layer of skin.

The trench kept collapsing. The generator kept choking. The grant was already half-spent and the university wanted results by Christmas — “deliverables,” they called them, as if the earth owed us neat packages of antiquity.

I’d been at this long enough to know that most of archaeology isn’t discovery. It’s negotiation: with weather, with budgets, with the slow indifference of time.

Sometimes I think the past resists us — not out of malice, but out of exhaustion.

My team had gone back to the prefab lab to upload soil data, so it was just me, a trowel, and a slab of Northumbrian silence. The kind of silence that hums if you listen too long.

You could hear the sheep on the next ridge. A crow somewhere. The low pulse of wind turbines to the west.

The ground smelled like iron and salt.

The peat was darker here — thicker — as if something once burned under it and never stopped smoldering.

I knelt by the trench, scraping at a stubborn patch of clay, and thought about my mother.

I always do, though I don’t call it that. It’s more like a rhythm under thought — her voice reading Latin aloud while I draw liver shapes on butcher paper.

Volterra, summer light through dust, the tang of copper tools.

She would say, “We listen to what the ground doesn’t say.”

That was before the collapse. Before I stopped listening.

The rain hit harder, drumming against my hood. I checked the time — 17:48. The sky already bruising toward night. The trench lights flickered once and steadied.

I wanted to go home — but home is a word that’s lost its coordinates. Durham feels borrowed, my father’s house hollow, my old flat in Rome long gone.

Everywhere I stand is a site. Everything I touch is temporary.

I took another slow pass with the trowel and found nothing.

No sherd, no coin, no context. Just the earth returning to itself.

For a moment I let myself imagine: if the Wall could speak, what would it say?

The thought was ridiculous, sentimental even. But it stayed.

Something beneath me — not a voice exactly, more like pressure, waiting.

I told myself it was fatigue.

Fatigue is the archaeologist’s constant god.

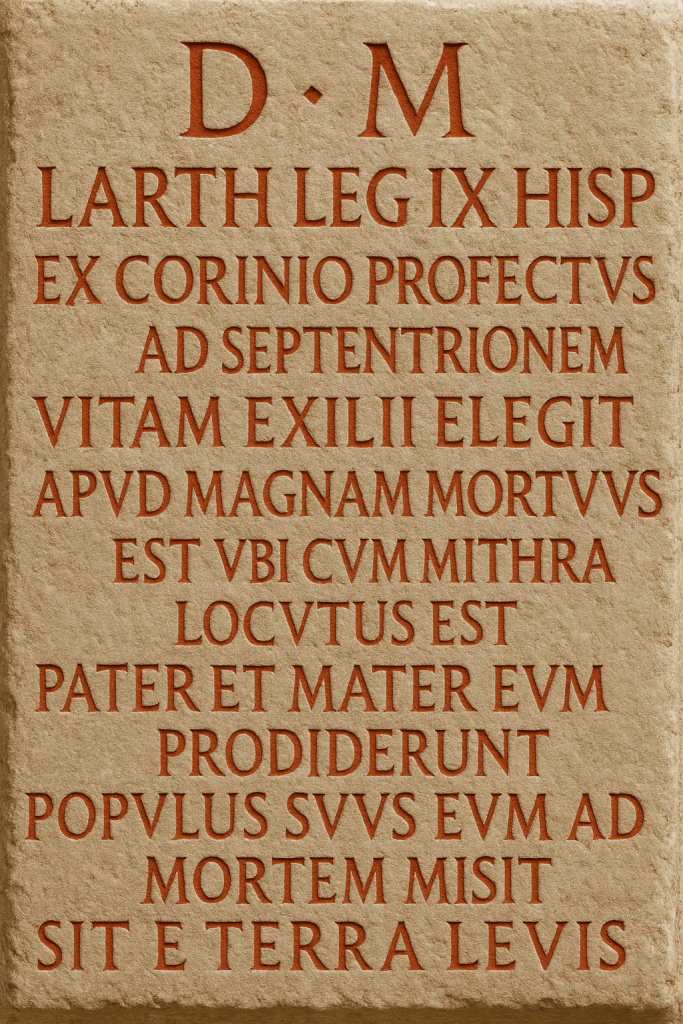

I stood, wiped my gloves against my trousers, and looked north. The mist was lifting. The outline of the old Mithraeum loomed just beyond the safety barrier — half exposed, half asleep.

That’s when I thought I heard it — a low hum through the ground, like a current running under my boots.

Then a heartbeat of stillness.

I crouched again. Pressed my palm flat into the mud.

The warmth startled me — not body heat, something deeper.

It was probably the generator.

It was probably nothing.

I didn’t know yet that I’d just touched the edge of a name.