of workers freed from king and creed

rose for a world that would not bow

We name the colours, forget the pain.

Taught without meaning, again and again —

Until we teach what freedom meant then

Refrain (spoken or sung softly)

Taught without meaning, again and again —

We name the colours, forget the pain.

I. The Flag of the Fields

Green, white, and red once dreamed of bread,

of workers freed from king and creed,

a flag that spoke of fields instead

of crowns and swords and noble need.

Taught without meaning, again and again —

We name the colours, forget the pain.

II. Guido Fawkes (1570–1606)

Guido Fawkes, born 1570,

was racked in chains beneath the floor;

his body torn for what he planned—

to strike the crown, to end the war.

They burned his name into the night,

and made his ashes holiday;

they light the sky, but never tell

whose body paid for that display.

Taught without meaning, again and again —

We light the fireworks, forget the men.

III. William Wallace (1270–1305)

William Wallace, 1270 born,

was dragged through London’s iron rain;

they broke his limbs to teach the law,

then scattered him by gate and chain.

Now children trace the Union’s cross,

and cheer the tales of crown and land;

they do not hear the cry he gave,

or feel the rope on freedom’s hand.

Taught without meaning, again and again —

We wave the banners, forget the chain.

IV. Thomas Paine (1737–1809)

Thomas Paine, of Norfolk born,

took pen against the crown of men;

Common Sense became his sword,

and liberty his citizen.

Thirteen stripes in red and white,

rose for a world that would not bow;

but stars can fade to painted signs

when none recall the vow.

Taught without meaning, again and again —

We pledge allegiance, forget the pain.

V. The Lesson

So teachers hang the flags on walls,

and speak of courage, not of cost;

they praise the kings, the saints, the wars—

and never ask what freedom lost.

Guido’s fire, William’s chain,

Thomas’s bright ink on history’s page—

they gave their flesh, their words, their names,

and we were taught to turn the page.

Final Refrain (stronger, slower)

Taught without meaning, again and again —

We name the colours, forget the pain.

Taught without meaning, again and again —

Until we teach what freedom meant then.

Commentary

The poem’s purpose

This poem is a meditation on how nations turn pain into pageantry, and how children are often taught to revere symbols whose histories they are never invited to understand.

It juxtaposes three moments of rebellion — Guy (Guido) Fawkes (1605), William Wallace (1305), and Thomas Paine (1776) — to trace a single lineage of resistance to hereditary power and state violence.

Each figure stands for a different kind of dissent:

Fawkes — punished by torture and death, remembered only as a villain or spectacle, his political motives flattened into a ritual of fireworks and obedience.

Wallace — executed publicly as a traitor, his body divided to warn others, yet later reabsorbed by empire as a symbol of “unity” rather than defiance.

Paine — a writer who used words rather than weapons, whose vision of liberty under reason and equality shaped the American Revolution — and yet, even his ideas have been domesticated into patriotic ritual.

By repeating the refrain “Taught without meaning, again and again,” the poem insists that history, in schools and in public life, is not neutral — it is curated forgetting. The refrain becomes a ritual undoing of that ritual: a call to remember the cost behind every colour and every flag.

The flags and their meanings

The first flag (green, white, red, with a wreath and quartered crosses)

This is the flag of the English People’s Republic — a speculative or symbolic banner imagined by anti-monarchists and republicans.

Green represents the land, labour, and renewal — the commons reclaimed from enclosure.

White stands for equality and peace between peoples.

Red evokes both the blood of the oppressed and the courage of revolt.

The wheat wreath signifies sustenance and work, the dignity of feeding oneself rather than serving a master.

The quartered shield bears crosses of England, Scotland, Ireland, and Wales — but they are no longer under a crown. They are held instead in the unity of the republic, bound by grain, not empire.

In the poem’s opening lines —

Green, white, and red once dreamed of bread,

of workers freed from king and creed,

the flag becomes an emblem of a different Britain — one that might have been and could still be, one built not on rule but on shared labour.

The second flag (thirteen stars and stripes)

The Betsy Ross flag — the first flag of the United States (1776–77).

Originally a symbol of liberation from monarchy, it is now a paradox: a revolutionary emblem that later flew over empire.

In the poem, the stanza about Thomas Paine (1737–1809) reminds us that the American Revolution was first a revolt of ideas — the conviction that freedom is born from reason, not lineage.

But the poem’s final lines about this flag —

Yet even there the children learn

the flag, not hunger, truth, or pain

— reveal how even rebellion can harden into myth. The flag once stood for emancipation; now it often stands for power itself.

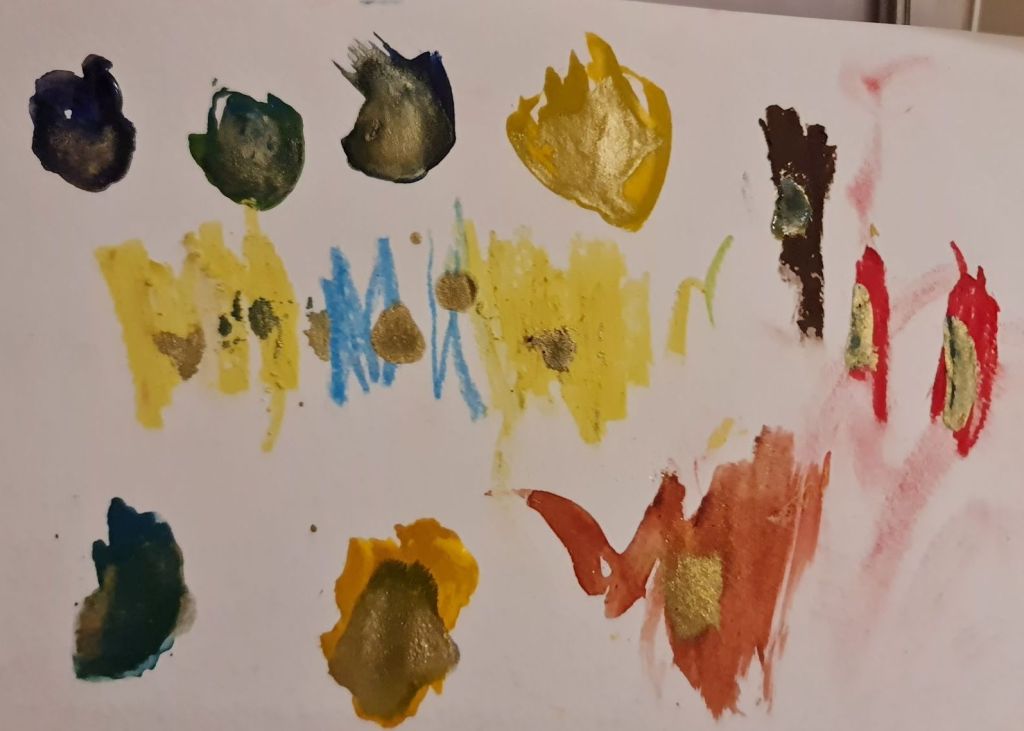

Cinnamon’s painting

Cinnamon’s painting — a child’s vision using those same colours and symbols — becomes the heart of the poem’s moral.

Where adults teach flags as abstractions of loyalty, a child paints them as shapes of feeling: colour without propaganda, form without coercion.

Her work reclaims the right to look — to re-see — before the meanings are imposed.

In the context of the poem, Cinnamon’s act of painting the flag is the antidote to the refrain “Taught without meaning.”

Where the system teaches forgetting, the child reimagines.

Where history flattens complexity, the child restores ambiguity and empathy.

Cinnamon’s use of green, white, and red echoes the idea of life, balance, and courage — but stripped of state ideology. In her painting, those colours are no longer a regimented banner; they are living pigments, a field of imagination.

If the poem mourns the loss of meaning, her art rebuilds it — intuitively, freely, outside the grammar of indoctrination.

4. The central paradox

The poem does not glorify violence or rebellion.

It asks: Why are the violent acts of states celebrated, while the rebels who challenged them are vilified or sanitized?

By naming dates, it situates each act of suppression in time, then asks how time itself was manipulated to make those acts appear inevitable, righteous, or distant.

The final refrain —

Taught without meaning, again and again —

Until we teach what freedom meant then.

— offers a simple ethical task: not to erase flags, but to explain them truthfully; not to reject symbols, but to ensure children know whose voices were silenced behind them.

5. In Cinnamon’s name

Cinnamon’s presence in this work — as daughter, painter, learner — gives the poem its emotional grounding.

It is written not to turn her against her peers or teachers, but to give her the language of awareness: that every story has another side, every celebration has a cost, and every colour on a flag once belonged to someone’s body, someone’s field, someone’s dream.

Where the system teaches uniformity, Cinnamon’s act of questioning restores the oldest human right — to see clearly, and to choose what the colours mean.